Periacetabular Osteotomy

Periacetabular Osteotomy

Hip Dysplasia & Periacetabular Osteotomy

Hip dysplasia is a disease of abnormal development of the femoral head and hip socket. It can be caused by multiple underlying conditions with the common finding of abnormal positioning of the femoral head relative to the hip socket. The main risk factors are female sex, family history, certain conditions during the mother's pregnancy, and certain ethnic groups. The cause of hip dysplasia is not clearly known but is thought to be due to a predisposition of soft tissue laxity (looseness) which causes the femoral head to move away from the hip socket during childhood. Gradually the femoral head can even completely dislocate from the hip socket.

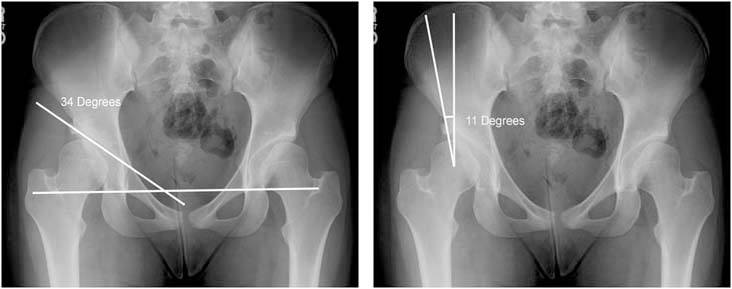

Normally, the hip socket or acetabulum develops its shape in response the head of the femur. If the head of the femur is positioned abnormally, the acetabulum can form with an angulated roof that slopes upward. This can lead to increased pressures on the cartilage of the hip as well as a persistent tendency for the femoral head to slide in and out of the hip with daily activities. This mechanical problem leads to a greater tendency to develop arthritis in middle age.(See Figure 1 )

During childhood, hip dysplasia can be detected as a newborn using specialized tests performed by the pediatrician. If there is any question based on the presence of a hip "click" or on the examination, an ultrasound can be performed. Standard radiographs (X-rays) can also be helpful in making the diagnosis. The treatment of hip dysplasia in childhood depends on the age of the diagnosis. In very young children, harnesses or casts can be used to maintain the hip in the socket. If this is not successful, surgery is required to place the femoral head back in the socket and possibly to cut the bones to allow the hip to become more stable. Hip dysplasia that is untreated can cause significant disability for patients including hip pain, labral tears, and progression to hip arthritis at a young age. If residual findings of hip dysplasia persists after the age of 15 to 16 years old and the hip becomes symptomatic, other surgical options may be considered. These would include further realignments of the pelvis or femur called osteotomies. An osteotomy is any operation where a bone is cut and realigned. The Bernese Periacetabular Osteotomy is our preferred technique for correction of acetabular deformities in patients who are skeletally mature. If there is also a deformity of the femur, this procedure can be combined with a realignment of the femur called a femoral osteotomy.

Figure 1: Comparative radiographs of the pelvis from a 30 year old female with hip pain and early hip dysplasia (left) and a 49 year old female with underlying hip dysplasia (right) with progression to full-blown advanced hip osteoarthritis. This patient has since undergone hip replacement on both sides.

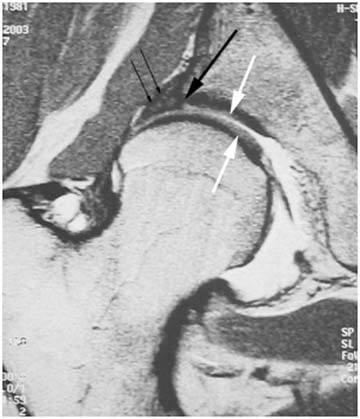

In younger patients, this abnormality can lead to increased pain in the hip as well as tears of the labrum. When this condition is diagnosed in adulthood and the hip is still in the non-arthritic phase, there is still a chance to intervene prior to full blown arthritis. Standard radiographs only show the damage in its final stages. Newer types of studies such as MRI (See Figure 2) can show early damage to the structures in the hip.

Figure 2: MRI of a hip with dysplasia showing much of the head uncovered by the bony roof (roof edge shown by large black arrow). The other structures of the joint such as the cartilage (large white arrows) and an enlarged labrum (small black arrows) can also be seen on the MRI image.

Our goal is to do something prior to the need for hip replacement because of our philosophy that your own joint is far superior to a mechanical joint regardless of what artificial material is used. Fortunately, there are some options available if the patient presents early enough.

Periacetabular Osteotomy

The most successful, safe, and predictable of these operations is termed the "periacetabular osteotomy", also called the "PAO". It was developed by two ingenious surgeons, Professor Reinhold Ganz and Dr. Jeffrey Mast in the early 1980’s. An osteotomy is the surgical division of a bone and periacetabular described the application of the osteotomy "around" the hip socket or “acetabulum”. The procedure involves making a series of angular cuts on the pelvis, separating the hip socket from the pelvis and allowing free rotation of the socket in three dimensions. It has proven to be one of the most effective surgical procedures in the treatment of hip dysplasia in adults. The major advantage of the procedure is the flexibility of placement of the hip socket in essentially any position and the preservation of the stability of the pelvic ring. The ability to freely position the hip socket gives your surgeon the ability to customize the correction of the anatomy to the specific deficiencies of that pelvis.

Computer Assisted Preoperative Planning of PAO

We have been using three dimensional reconstructions to make a very precise computer model of the pelvis. (See Figure 3) With this information and a large database of normal pelvis models, we are able to plan the reorientation of the hip socket to as close a normal position as possible even before the operation. The preoperative computer plan is correlated with intraoperative xrays which allow for a very precise correction. The other benefit of the PAO is the innate stability of the hip socket at the end of the procedure.

Figure 3: Computer Generated Three-Dimensional Model of Pelvis With Hip Dysplasia both Before (left) and After (right) Simulated PAO.

Advantages of PAO

After PAO, patients can bear weight much earlier than with other procedures and females who undergo the procedure can have normal future vaginal deliveries rather than requiring a Cesarean section.

Recovery After PAO

Most patients require hospitalization for 3 to 4 days and can get up with physical therapy on the day after the procedure. Crutches or a walker are usually continued for 6 weeks until there is some evidence of healing of the osteotomy site. After the 6 to 8 week mark, if there is evidence of healing of the osteotomy site on the xrays, patients can resume weightbearing. In many cases, they may have some slight muscle weakness which responds well to physical therapy. By three to four months, nearly everyone walks without a cane. The most gratifying part of the operation is to see patients return to high level activities and occupations without even thinking about their hip.

Potential Complications After PAO

Although the PAO is a relatively major hip operation, in many ways, it is the safest in the long run. The biggest risks are from damage to the nerves, arteries, or veins that run in the pelvis. This risk is minimized by performing all the cuts with full xray guidance in the operating room as well as extensive experience with the operative procedure.

Periacetabular Osteotomy FAQ

1. What does periacetabular osteotomy (PAO) mean?

The term periacetabular osteotomy means a surgical procedure involving the cutting of bone around the acetabulum (the hip socket)

2. Who developed this procedure?

The procedure was developed by Prof. Reinhold Ganz, an orthopaedic surgeon in Switzerland and Dr. Jeff Mast, an American orthopaedic surgeon.

3. Who would benefit from this operation?

The indications for the procedure include any patient with a mechanical abnormality of the hip secondary to malpositioning of the hip socket.

4.How does cutting the bone and moving things help my hip pain?

The theories of hip pain include instability of the hip due to lack of containment of the femoral head, excessively high pressures within the hip due to poor coverage of the femoral head, and abnormal contact or impingement of a portion of the femur with that of the hip socket (acetabulum).

5.Why not just have a total hip replacement instead of going through with this operation?

A total hip replacement is a major procedure with substantial restrictions of activity, numerous potential modes of failure, progressively declining success at each revision (repeat hip replacement). If a patient were to have hip dysplasia and undergo a total hip replacement in their thirties, there is a very high probability that they would need at least one to two further repeat hip replacements. Each time that this is performed, the patient would have a higher risk of losing bone, getting an infection, having a longer operation time, more blood loss, and other risks. The ultimate goal of orthopaedic surgery is to maintain the patient’s own joints until they can no longer function. A periacetabular osteotomy has been shown to increase function, decrease pain, while avoiding some of the long-term risks associated with joint replacement. As far as activities, a periacetabular osteotomy would give the patient a higher chance of resuming very vigorous activities that would be precluded for a total hip replacement.

6.How long is the recovery?

The procedure involves the cutting of the pelvis at specific points with complete mobilization of the hip socket. The socket is then fixed in place with screws. Post-surgical weightbearing is restricted for at least 6 weeks and sometimes longer until there is evidence of healing on the x-rays.

7.I am a young female... Will I be able to have children after this procedure?

One of the major advantages of this procedure over other types of pelvic osteotomy is the minimal effect on the birth canal. Most patients are allowed to have a normal vaginal delivery if they become pregnant at some point after undergoing PAO.

8.What is the success rate with this operation?

The success rate depends on a number of factors. First and foremost, the need for conversion to a total hip replacement at some time in the future is related to the degree of arthritis present in the joint at the time of the osteotomy. Other factors include the degree of deformity and the degree of correction achieved. Overall, if the hip has little to no arthritis, the success rate for avoiding a hip replacement is greater than 90% for at least ten years if not longer.

9.What are the complications of this operation?

There are a number of complications. Overall, however, the major complication rate is about one out of fifty cases. The most common minor complication rate is some numbness on the outer part of the hip from stretching of a nerve called the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve. This numbness rarely causes any problem for patients and the area of numbness usually gets smaller with time. Other complications include the risk of bleeding from the vessels within the pelvis, the risk of damage to nerves including the sciatic nerve which supplies many muscles in the leg, risk of the bones not healing properly or displacing, the risk of entry of the chisels used for the osteotomy into the hip joint itself, risk of infection (about 1%), the risk of anesthesia, risk of blood clots in the leg (deep vein thrombosis) or in the lung (pulmonary embolism), as well as other potential complications.

10.How long will I be in the hospital?

Most patients are in the hospital for 4-6 days.

11.How long will I need crutches?

Crutches are required for at least 8 weeks. Most patients are walking without any walking devices such as canes by the three month visit.

12.How often will I be seen in follow-up?

Patients are seen early on after their surgery to check the wound. They are then seen at 6 weeks, three months, 6 months, and then at one year.

13.What if the operation fails and I develop hip arthritis?

In the unlikely event that the operation were not successful and the hip goes on to arthritis, in many cases, patients report a high rate of satisfaction for several years after the operation. A total hip replacement can then be performed with minimal effect from the previous osteotomy. Another important factor is that every year new technology is available to make hip replacements last longer and preserve more bone for the future. Additionally, with time, medical research achieves greater and greater understanding about the response of the human body to joint replacements. Thus, delaying a hip replacement if at all provides these advantages to the patient.

PERIACETABULAR OSTEOTOMY SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

The goal of periacetabular osteotomy is to reorient the acetabulum (hip socket) in order to minimize contact pressures on the hip joint as well as to help contain the femoral head and avoid an unstable joint.

1.This patient's pelvis radiograph (Left) demonstrates hip dysplasia and is compared to a normal pelvis radiograph (Right). The hip dysplasia is more advanced on the right side where the acetabular labrum has been damaged and actually been converted to bone (arrow). The roof of the acetabulum is sloped upward leading to increased pressure within the hip and an increased tendency for the head of the femur to be unstable within the hip joint. This is termed hip subluxation. The presence of increased contact pressures and hip instability leads to hip arthritis in many patients with hip dysplasia.

2.The acetabular index is a measurement of a line formed parallel to the weightbearing zone and the line connecting the base of both hip sockets. In this case it measures 34 degrees. The normal measurement is approximately 6 degrees. A second measurement used in the evaluation of hip dysplasia is called the Center-Edge angle (CE angle). It is measured by drawing a line vertically through the center of the femoral head and a second line from the center of the femoral head to the edge of the hip socket. The angle between these two lines is the Center-Edge angle. In this case, it measures 11 degrees. The normal value for the CE angle is greater than 20 degrees.

3.The images above are specialized MRI images taken from a procedure called MRI arthrography where a specialized material is injected into the hip joint and an MRI is obtained. These show the damage to the acetabular labrum as well as demonstrating the minimal coverage of the femoral head.

4.In this patient, we recommended a periacetabular osteotomy. In the photograph above, the muscular interval between the sartorius (SA) muscle and the tensor fasciae latae (TFL) is utilized. The sartorius muscle originates from the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS).

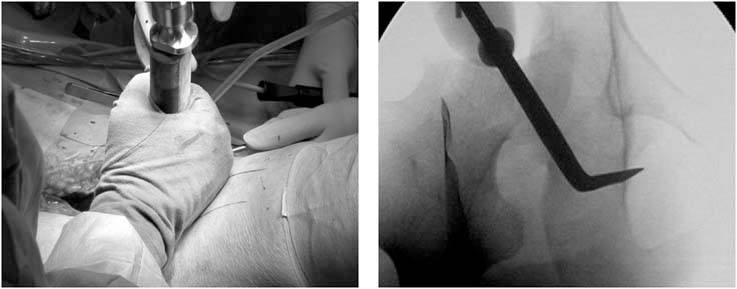

5.A special angled bone cutting tool (osteotome) is used to cut the ischium bone behind the hip joint as shown in the upper image of the two images above. The image on the bottom of the two images above is an intraoperative live radiograph which shows the position of this osteotome.

6.After the cut on the ischium bone, the pubis bone is cut with a chisel (shown on this radiograph). Next a cut is performed on the ilium bone and this is connected to the partial cut of the ischium bone. The fragment containing the hip socket is then completely separated from the pelvis. A pin shown on the surgical photograph on the right is used to position the hip socket in an optimal configuration using intraoperative radiographs.

7.Once the optimal position is achieved the fragment containing the hip socket (arrow) is held in place with smooth wires from the top of the ilium bone.

8.Bone graft obtained during the bone cuts is the used to bridge the triangular space created by the configuration. This bone graft remodels over time to form a sturdy bone bridge across the cut bone.

9.This is the final radiograph demonstrating the correction of the deformity and the position of the hip screws used to stabilize the cut bone fragment which contains the hip socket.

References

- Wiberg G. Shelf operation in congenital dysplasia of the acetabulum and in subluxation and dislocation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. Jan 1953;35-A(1):65-80.

- Lequesne M, de S. [False profile of the pelvis. A new radiographic incidence for the study of the hip. Its use in dysplasias and different coxopathies]. Rev Rhum Mal Osteoartic. Dec 1961;28:643-652.

- Sharp IK. Acetabular Dysplasia, The Acetabular Angle. J Bone Joint Surg Am. May 1961;43-B(1):268-272.

- Murphy SB, Kijewski PK, Millis MB, Harless A. Acetabular dysplasia in the adolescent and young adult. Clin Orthop Relat Res. Dec 1990(261):214-223.

- Murphy SB, Ganz R, Muller ME. The prognosis in untreated dysplasia of the hip. A study of radiographic factors that predict the outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. Jul 1995;77(7):985-989.

- Lequesne MG, Laredo JD. The faux profil (oblique view) of the hip in the standing position. Contribution to the evaluation of osteoarthritis of the adult hip. Ann Rheum Dis. Nov 1998;57(11):676-681.

- Sugano N, Noble PC, Kamaric E, Salama JK, Ochi T, Tullos HS. The morphology of the femur in developmental dysplasia of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. Jul 1998;80(4):711-719.

- Hipp JA, Sugano N, Millis MB, Murphy SB. Planning acetabular redirection osteotomies based on joint contact pressures. Clin Orthop Relat Res. Jul 1999(364):134-143.

- Noble PC, Kamaric E, Sugano N, et al. Three-dimensional shape of the dysplastic femur: implications for THR. Clin Orthop Relat Res. Dec 2003(417):27-40.

- Dandachli W, Kannan V, Richards R, Shah Z, Hall-Craggs M, Witt J. Analysis of cover of the femoral head in normal and dysplastic hips: new CT-based technique. J Bone Joint Surg Br. Nov 2008;90(11):1428-1434.

- Fujii M, Nakashima Y, Yamamoto T, et al. Acetabular retroversion in developmental dysplasia of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. Apr 2010;92(4):895-903.

- Troelsen A, Romer L, Jacobsen S, Ladelund S, Soballe K. Cranial acetabular retroversion is common in developmental dysplasia of the hip as assessed by the weight bearing position. Acta Orthop. Aug 2010;81(4):436-441.

- Anderson LA, Gililland J, Pelt C, Linford S, Stoddard GJ, Peters CL. Center edge angle measurement for hip preservation surgery: technique and caveats. Orthopedics. Feb 2011;34(2):86.

- Fujii M, Nakashima Y, Sato T, Akiyama M, Iwamoto Y. Pelvic deformity influences acetabular version and coverage in hip dysplasia. Clin Orthop Relat Res. Jun 2011;469(6):1735-1742.

- Paliobeis CP, Villar RN. The prevalence of dysplasia in femoroacetabular impingement. Hip Int. Apr 11 2011;21(2):141-145.

- Stubbs AJ, Anz AW, Frino J, Lang JE, Weaver AA, Stitzel JD. Classic measures of hip dysplasia do not correlate with three-dimensional computer tomographic measures and indices. Hip Int. Sep-Oct 2011;21(5):549-558.

- Akiyama M, Nakashima Y, Fujii M, et al. Femoral anteversion is correlated with acetabular version and coverage in Asian women with anterior and global deficient subgroups of hip dysplasia: a CT study. Skeletal Radiol. Nov 2012;41(11):1411-1418.

- Fujii M, Nakashima Y, Sato T, Akiyama M, Iwamoto Y. Acetabular tilt correlates with acetabular version and coverage in hip dysplasia. Clin Orthop Relat Res. Oct 2012;470(10):2827-2835.